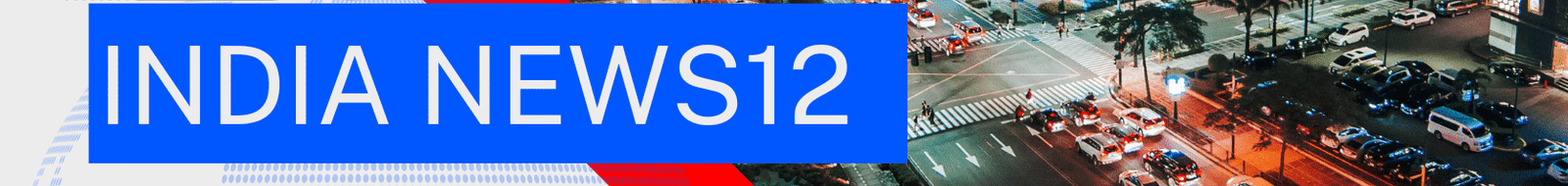

By the time Jasprit Bumrah arrived in Melbourne for the fourth Test of the Border-Gavaskar Trophy, he had already bowled 88 overs – 528 deliveries. In the first innings at the MCG, he added 28.4 overs more to his tally.

With a World Test Championship final berth on the line, the series carried immense significance for India. Captain Rohit Sharma had to win the fourth Test to take a 2-1 lead going into the fifth match.

On day four, Bumrah, India’s lead bowler in the series, sent down 24 overs across three sessions, coming in for nine short bursts of spells. By the evening session, Bumrah was visibly fatigued and conveyed the same to his captain, Rohit: “Bas ab, aur nahi lag raha zor (Enough, I can’t push anymore),” the stump mic picked up.

He bowled four more deliveries, finishing with a career-high 53.2 overs in a Test. Three days later, Bumrah was back on the field in Sydney. However, he could only bowl 10 overs before experiencing back spasms and did not take the field for the rest of the match.

Across 45 days, the speedster bowled 908 deliveries — not counting those in training. It was later revealed that the pacer had a stress-related lower back injury in the same region where he had an issue that ruled him out for 11 months in 2022–23.

“As is often the case, when a bowler’s performing well, there’s a natural reluctance – from both player and team – to slow things down,” says Andrew Leipus, former physiotherapist with the India team and current Punjab Kings physiotherapist consultant.

Fast bowling is a high-load activity. Each delivery places several times the force through the lumbar spine. What Bumrah suffered was a lumbar stress injury – a precursor to what’s medically defined as a stress fracture in the lumbar region.

“A lumbar stress fracture represents the most severe end of what’s known as the bone stress injury (BSI) continuum,” Leipus explains. “Put simply, bone is a living, adaptable tissue that responds to mechanical load. When the stress placed on it consistently exceeds its ability to recover and adapt, the breakdown process outpaces repair, eventually leading to a cortical fracture.”

From 1999 to 2004, Andrew Leipus served as India’s physio and helped raise the team’s fitness standards across the board managing players like Venkatesh Prasad, Javagal Srinath, Ajit Agarkar and Zaheer Khan.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Library

From 1999 to 2004, Andrew Leipus served as India’s physio and helped raise the team’s fitness standards across the board managing players like Venkatesh Prasad, Javagal Srinath, Ajit Agarkar and Zaheer Khan.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Library

Bowling pace is inherently risky; not every injury is avoidable, and sometimes even well-managed workloads can lead to breakdowns. But in most cases, patterns of mismanagement are clear and avoidable.

Leipus says that the progression of a BSI to a fracture in a pacer is rarely caused by a single factor. “They’re typically the result of a complex interplay between biomechanics, workload errors, and systemic gaps in preparation or monitoring,” he explains. Add to it: the player’s age, bowling experience, various physical attributes, and individual biomechanical issues.

Ian Pont, head coach and founder of the National Fast Bowling Academy in the United Kingdom, doesn’t find a problem in Bumrah’s action, which he describes as “unique and biomechanically efficient.”

“He did suffer injuries, but they weren’t due to his action – more due to workload mismanagement; excessive play without rest,” Pont, who has coached in India for over 15 years, says.

Rest and recovery are crucial aspects of a fast bowler’s longevity. If the pacer is tired, fatigued, or sore, physiotherapists usually take it as a red flag for a stress reaction. Workload management is the science of planning how many balls a bowler delivers, how often, and at what intensity.

“It is the key to keeping bowlers injury-free and performing well over time. Done right, it extends careers and prevents stress fractures. Done poorly, it leads to injury, rehab, and re-injury cycles,” Pont says.

According to Pont, the support staff – bowling coach, physiotherapist, and strength and conditioning coach – should take note of each delivery a pacer bowls, during a game and while training. “Increase weekly workload gradually,” he says. “No more than a 20 per cent jump week to week. For example, going from 60 to 100 balls weekly too quickly raises injury risk.”

Body physiology and mechanics

Bumrah’s case isn’t an isolated one. A decade ago, a young Indian speedster too found himself in a loop of back injuries.

By 2012, promising fast bowler Varun Aaron had developed a recurring back injury that had already ruled him out of India’s 2011 tour to Australia and limited his participation in the Indian Premier League (IPL), where he was representing Delhi Daredevils (now Delhi Capitals). He eventually underwent surgery, which sidelined him for nearly 16 months.

“I had eight stress fractures in my back and three in my foot – so, 11 in total,” Aaron says. According to the pacer, body physiology is one of the contributing factors for such injuries. “If your body is predisposed to taking extra load in one part – say, your back – you’re more likely to suffer injury. I was born with an exaggerated arch in my back, called lordosis. Because of that, my spine hinges at the L3 vertebra. My first three or four fractures were in that region.”

In a country starved of genuine pace, Varun Aaron stood out in the early 2010s, regularly clocking over 145 kmph. But recurring back injuries — the price of bowling fast — cut his career short.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Library

In a country starved of genuine pace, Varun Aaron stood out in the early 2010s, regularly clocking over 145 kmph. But recurring back injuries — the price of bowling fast — cut his career short.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Library

Certain bowling actions increase this stress, particularly mixed actions (part front-on, part sideways). “In biomechanics, problems arise when there’s too much counter-rotation in your bowling action – when your hips and shoulders don’t align,” the now 35-year-old Aaron explains.

He believes that bowling coaches play a crucial role in the rehab process – a detail often overlooked. “Stress fractures happen because your body is absorbing load unevenly. Fast bowling is inherently unilateral – one side always bears more load. But if you can streamline your action efficiently, you reduce the risk of injury,” Aaron explains.

For Pont, the role of a bowling coach is crucial in a bowler’s life right from the grassroots, since the bodies of athletes under the age of 25 are still developing. “Fifteen to 19 years of age is the highest incidence of lumbar stress fracture,” he notes. “It’s the most vulnerable age group since spines are still developing – vertebrae don’t fully ossify until around 21–23 years.”

Young bowlers often play year-round with high workloads but underdeveloped strength and poor recovery habits. If coupled with poor technique, this creates a perfect storm for injury. A study on English County Cricket fast bowlers between 2010 and 2016 showed that 368 pacers reported 57 lumbar stress fractures, with a mean age of 22.8 years.

“Coaches don’t often adjust the technique, especially at the club and low level. I don’t blame them; they probably don’t know this stuff. So, they will revert the bowler to the same mixed action or flawed posture. Without technical and biomechanical correction, the injury risk remains the same,” Pont says.

Aaron was 22 when he had his eighth stress fracture. And it was during the rehab after his surgery that he realised his old action needed to be tweaked. “I stopped getting stress fractures once I made the right biomechanical adjustment,” he says. “That was my last fracture,” he adds.

Fast and furious

A 21-year-old, Mayank Yadav, took everyone by surprise by consistently clocking speeds over 150 km/h when he made his IPL debut in 2024. His fastest delivery saw the speedometer touch 156.7 km/h – the second-fastest for an Indian after Umran Malik’s 157 km/h thunderbolt in the 2022 season. Umran had also made his IPL debut at 21 years in 2021 for Sunrisers Hyderabad.

While the explosive pace drew immediate attention, it also came with physical consequences.

Mayank managed just four games for Lucknow Super Giants before a back injury ruled him out. He returned in October to make his T20I debut for India. But, much to his misery, he took another trip to BCCI’s Centre of Excellence (formerly NCA) owing to the same injury.

“Mayank and Umran Malik have fast, exciting actions but with high spinal loads and injury risk,” Pont notes. “Modifying them slightly to reduce spinal twisting or increase load sharing can reduce the injury risk,” he adds.

Mayank’s highly anticipated return in IPL 2025 was delayed due to his extended rehab programme. He eventually arrived, played two games, before his injury reappeared, ruling him out of the season. Umran, too, was sidelined due to a hip injury.

Mayank’s highly anticipated return in IPL 2025 was delayed due to his extended rehab programme. He eventually arrived, played two games, before his injury reappeared.

| Photo Credit:

EMMANUAL YOGINI

Mayank’s highly anticipated return in IPL 2025 was delayed due to his extended rehab programme. He eventually arrived, played two games, before his injury reappeared.

| Photo Credit:

EMMANUAL YOGINI

“Bone density drops significantly in and around the spinal segment after a stress fracture,” John Gloster, Rajasthan Royals’ head physiotherapist, says. “Bowlers are usually sidelined for 4–6 months, but bone density remains low for 6–10 months after recovery, heightening re-injury risk.”

Gloster believes there’s excitement when a 150 km/h fast bowler comes along, but managing them requires restraint. “Overexcitement can lead to overbowling.”

India hardly produces speedsters like Aaron, Mayank, and Umran, who can touch 150 km/h consistently. So, when they come along, there is a tendency to rush them into the system. “There’s a scarcity mindset. As soon as someone clicks 150 km/h, particularly in India, they are treated as a rare asset. Selectors and franchises feel they must get as much as they can, and quickly, before they get injured or drop form,” Pont opines.

“In the IPL, there’s a lot of franchise pressure. The teams see raw pacers as match-winning weapons. Young pacers can suddenly go from bowling 10 to 12 hours a week at full speed to three days with little build-up. There’s pressure on these guys to keep bowling faster. There’s a lack of patience and long-term planning,” he adds.

Leipus worked with the Indian team from 1999 to 2004 and says the landscape has changed dramatically since. “Workload tracking is better understood and more sophisticated, and treatment modalities and interventions have evolved so we can mitigate injury recurrence,” notes Leipus, who has also worked with Kolkata Knight Riders in the past.

The IPL typically spans from late March, concluding the international calendar, to late May, which marks the onset of the new cricket season. Several international players arrive after finishing a series and leave the tournament to join the national team, hardly getting a chance to rest. Most often than not, there is a change in format almost immediately.

Ian Pont, founder of the UK’s National Fast Bowling Academy, emphasises the importance of tracking every ball a pacer bowls — in matches and training — to manage the workload effectively.

| Photo Credit:

K. Bhagya Prakash

Ian Pont, founder of the UK’s National Fast Bowling Academy, emphasises the importance of tracking every ball a pacer bowls — in matches and training — to manage the workload effectively.

| Photo Credit:

K. Bhagya Prakash

“Switching formats on short notice is incredibly demanding, especially for fast bowlers,” Leipus says. “Test match bowling is about volume, rhythm, and control. T20 demands are almost the opposite – explosive spells, variation, and max effort. That quick pivot can be a challenge to the body if not managed carefully. T20s themselves aren’t the problem – it’s the transition without a buffer. And vice versa.” When players arrive for the two-month high-intensity tournament, the team management already has data about each individual, tracking everything from workload to fitness.

“Throughout the year, we collect insights through relationships with respective boards, handovers, GPS data, and nutrition reports. When bowlers arrive, we already have a clear picture,” Gloster says. “If a player is fatigued or not sleeping properly, that’s a risk. While we don’t control their training year-round, we use the data we have to tailor management plans during the IPL,” he adds.

Gloster believes that bowlers are often blamed when they break down while bowling, but the problem often starts in other areas of their training. “Poor gym training – lifting incorrectly or lifting too heavy – also contributes. When assessing workload, we must consider both bowling and gym activities.”

“For fast bowlers, the focus should be on building a strong, responsive posterior chain and legs, maintaining core stability, and preserving mobility – not just adding muscle mass. When spinal loading is poorly managed in the gym, it adds to the cumulative stress on the body and can tip the balance toward injury,” Leipus opines.

The teams screen each player on arrival before they are allowed to start practising to ensure their readiness. “Often, we have to resist the temptation to over-train in short camps, yet, on occasion, also have to remind them that they might be behind on their training at times. Ironically, under-training occurs more frequently than over-training during the IPL,” Leipus explains.

It all comes down to the coordination between the bowling coach and the physiotherapist. “It’s a combined effort. Having a good relationship with the coaching staff – understanding their expectations and how much they need the bowler to bowl – is vital.

We might say a bowler needs to bowl four overs in training, but the coach may want him to bowl eight to perfect his skills – say, yorkers. That’s a potential source of trouble,” Gloster says.

Prepare for the long haul

Post his breakdown in Sydney, Bumrah missed the ICC Champions Trophy 2025 and the initial four matches of IPL 2025 for the Mumbai Indians. Despite being named the vice-captain of India during the recent Australia tour and stand-in captain of the final Test, Bumrah’s injury woes have forced selectors to not burden him with more responsibility for the upcoming England tour. “We need him more as a player. We would rather have him bowling than putting extra pressure on him,” India’s chief selector Ajit Agarkar said during a recent press conference.

He also confirmed that Bumrah won’t be playing all five Tests owing to workload management. “I don’t think Bumrah will play all five Tests – whether it’s four or three – we’ll see how the series goes.”

Bumrah’s – or rather any fast bowler’s – case study is a cautionary blueprint. It’s a team’s responsibility to treat workload like a Test match: plan for the long haul, don’t burn out talent early.

Pont puts it perfectly: “It is about protecting the bowler from the game, not protecting the game from the bowler.”